The History of Great Canfield

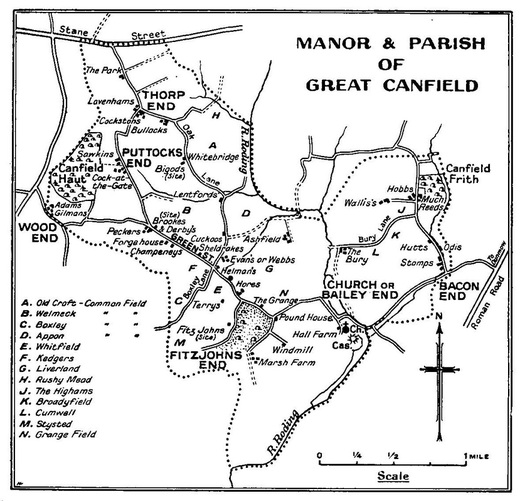

The Settlement (Source of sketch opposite: At the Courts of Great Canfield, G Eland, Oxford University Press, 1949)

From early times the richness and fertility of the land have attracted people to the location we now know as Great Canfield. A great diversity of relics has been unearthed, with the earliest a Neolithic polished stone axehead, dating from 3,500 BC. Artefacts from Celtic times and the Roman occupation onwards have been found in quantity. Many of these are in private collections and some are held in Saffron Walden Museum.

There is also archaeological evidence of Roman settlement, unsurprising as Great Canfield lies between two Roman roads that converge not far away. Hundreds of years after their construction the Normans reused bricks from local Roman villas in the fabric of the church.

The name Canfelda probably derived from "field of canes or reeds", perhaps linked with the marshy ground of the Roding valley. George Eland in his book "At the Courts of Great Canfield" suggested that the name Thorpe (Hope) End, a name retained into the C19th, hints at Danish occupation of that hamlet in 878. The Domesday Book of 1085 makes it clear that at the time of the Norman invasion Canfield formed a small part of the vast estates owned by Ulwine, a great Saxon thane.

Shortly afterwards Alberic de Vere was awarded the manor, and it remained in his family (later the Earls of Oxford) for five hundred years. The Normans built the castle mound, its outer bailey dating back to the early C12th, and the adjacent church of St Mary. The castle buildings were of wood. They and the palisades that surrounded them disappeared long ago, probably reapplied to dwellings elsewhere in Great Canfield. The farms around the church were demesne lands (farmed by serfs on behalf of the Lord of the Manor and not tenanted). The Hall, Canfield Bury and Marsh Farm now occupy some of that area.

Inside the church, acknowledged as a perfect example of Norman architecture, is a C13th mural of the Virgin and Child. In the porch are carvings from Norse mythology, adopted for Christian use, including Odin with his ravens Hugin and Mugin and depictions of a form of swastika, an ancient symbol also known as a fylfot cross.

The Parish and Manor seem always to have coincided in extent and the surviving manorial rolls help to explain the growth of the village over time. As the settlement evolved it developed a pattern still recognisable today. The Hart and Frith (or Thrift) Woods, both classified as Ancient Woodland, are now much diminished. They, together with the enclosed deer park which extended around Canfield Park House offered important economic rights and resources. Other woodland was cleared and the field system grew. In mediaeval times, large open fields ran down the middle of the village to the north and east of Green Street, with Bexley (or Boxley) Common to the west of it. Some of the ancient field names are still used.

After the C12th there is no evidence of any nucleus or dominant area, with a handful of farms and agricultural workshops being scattered throughout the Parish. Over the centuries, the seven distinct hamlets or Ends evolved around the farms, crofts and woods. The sketch at the foot of the page (from 60 years ago) shows the principal historical locations in the village, which survive to today with open countryside between them.

The church was always an important focus for the community but even in the Victorian period while almshouses lay close by the church, the inn, school and rectory were all situated separately from it. Shops, forge, maltings and post-office have all changed their locations over time. The stocks and whipping-post were situated centrally at Hellman’s Cross and The Griffin Inn was part of what is now The Grange.

As now, houses generally sat within their own plots, the majority accessed directly from the main lanes though often set back from them. Most originated as farmhouses or farm cottages, although the former were often divided into tenements in Victorian times. Until the break-up of the Maryon-Wilson Estate in 1900, few were owner-occupied.

It appears that from very early times the village adopted the linear character it still possesses. Its lanes linked the common lands and discrete parts of the manor with the major highway at Stane Street (now the B 1256), to the thriving market town of Hatfield Broad Oak and its Benedictine Priory, and other neighbouring settlements. In later centuries those lanes also provided links to Maryon-Wilson properties in other parishes, for example Langthorns in Little Canfield. A drove road is said to have originally run past The Elms which at one time sold ale to those who passed. As late as 1908 a new road was cut linking Bacon End with the railway station at Little Easton Lodge.

Within living memory the village still had a pub, school, post office, forge and shop but all have now reverted to other uses. Many houses large and small have been renamed. Others have simply disappeared, even quite recently, for example Whitebridge in Oak Lane where George Eland lived and wrote in the 1940s. There remain many other signs of earlier settlement in the form of listed dairies, pumps, dove-houses, model farm buildings, barns, and even a brick icehouse. Satellite photographs also reveal the outline of a windmill which was destroyed around 1900.

The People

By the time of Domesday the manor supported about 100 people including serfs. Tenant farmers were obliged to cultivate de Vere’s land but were also able to rent land for themselves and use the common land for grazing animals.

The records of the manorial court start in 1346, the year of the Battle of Crécy. They end in 1668, giving perspective over more than three hundred years of Great Canfield history. Occasionally the village felt the impact of great events from outside: most notably the records give evidence of exceptional mortality around the time of the Black Death in 1349. Otherwise they dealt with preoccupations arising locally. Apart from the odd assault and theft, most had to do with the land.

In the late C16th, the Wisemans acquired the title of Lords of the Manor. In the early C18th the title passed to the Peers family and from there by marriage and descent to the Maryon-Wilsons, who had acquired many holdings in the Parish. A family member still holds the title of Lord of the Manor.

Two books add detail on Great Canfield’s history. George Eland’s outlines findings from the manorial court rolls and discusses particular houses built during that time. Raleigh Trevelyan’s "A Hermit Disclosed" examines the life of Jimmy Mason, a recluse in Great Canfield, through the diary he kept a century and a half ago.

Great Canfield developed as a flourishing agricultural community. The population peaked at 520 in the early C19th. The census of 1831 showed virtually all working within the Parish and 80% of its working population still on the land. White’s Directory of Essex from 1848 describes Great Canfield as "a pleasant village … has in its Parish 496 souls and 2,471 acres of land". The Directory provides a list of inhabitants. It includes in addition to those working on the land a carpenter, victualler, wheelwright, shopkeeper, blacksmith, bricklayer, corn miller, tailor, vicar, and the squire. To these the Post Office Directory of 1874 adds a schoolmistress, shoemaker and farm bailiff to manage the squire’s estates – virtually everybody at that time still finding employment within the village.

In 1825 there were 93 houses in Great Canfield and by 1875 this number had risen to 122. It declined to 75 in the 1920s, possibly as divided tenements were once more combined into single dwellings whilst others just collapsed. From then on the number rose steeply again to the current 144 with much of this growth taking place in Hope End.

Great Canfield Today

Great Canfield has five main points of entry and is separated from its neighbouring villages by open farmland. The majority of houses back onto or are surrounded by agricultural land. This rural setting is greatly valued by the community, who strongly oppose urbanisation in its various forms.

Great Canfield remains a rural village, albeit one under pressure from urban development. Particularly in the Hope End and Bacon End areas, actual and planned developments in Takeley and Little Canfield grow ever closer.

At the time of the last census in 2001, there were 139 homes, including 3 council-owned and 23 privately rented with the remainder owner-occupied. Since that time there have been a number of barn conversions. The total number of homes has now risen to 144.

In 2001 there were 110 detached houses or bungalows, and 29 terraced or semi-detached residences. Of the total population of 364, 196 were male and 168 female. The age profile of Great Canfield’s residents was very similar to other local towns and villages. The current electoral register shows 311 voters.

A great demographic change occurred as agriculture shed its large labour force, and many houses originally occupied by farming or ancillary workers were no longer required for that purpose. Today the great majority of residents in work find employment outside the village and in the absence of any regular public transport, 96% of households have a car and 76% have two or more.

Great Canfield, as we were; The Vane Charity

In June 1866 the executors of the Reverend Frederick Vane invested £50 in three per cent annuities. The income was to be applied for the poor of the Parish of Great Canfield: on St Thomas’ Day, 21st December, a traditional day of charity in England and the shortestday of the year.

The population of Great Canfield 150 years ago was just under 500, 35% more than today. Virtually everyone worked within the Parish and 80% laboured on the land. Few people were likely to have had much money and life would have been pretty uncomfortable for some.

The Vane Charity was now able to help. Records for the Charity, contained in a small ruled exercise book, shed more light. Help was given mainly in coal. The first entry, on St Thomas’s Day 1866, had a half-year’s dividend of 17s 5d to distribute. “Coals to widows” accounted for 16s 6d and “Balance to Holdgate” the remaining 11d (d = old pence).

There are still Holdgates in the area. There appear many other family names, longstanding in the village and surrounding areas: Barker, Easter, Hayden, Perry, Reeve, Staines, Stock, and Lodge (probably the family of Isaac, born in 1866, who went on to win the Victoria Cross in the Boer War). Entries for male recipients in the early days usually just give surnames. Sometimes there is more to distinguish from others of the same name: Old Staines, Old Cliff, Blind Stock, Spellar’s boy, L Hayden. Many entries are generic: on St Thomas’ Day in 1869 the Charity gave 1ó hundredweight (76 kg) of coals each to “10 widows, 3 widowers and 5 sick people”. Sadly, there is no reference to where

anyone lived.

The yearly income of £1 14s 10d went a long way. One hundredweight of coal cost 1s 3d, a factor of about two hundred times less than today. The price hadn’t changed in 1906, when records in the exercise book ceased. There are few surviving records for a long time after 1906, but thanks to 70 years’ inflation the yearly income by 1976 no longer went far at all. The general pattern was now to let funds accumulate for a while and then make a contribution towards meals or fuel. In correspondence with the Charity Commission the then Rector noted “the quarterly interest, at present 36p, has been held as so small as to be incapable of regular distribution”. The volume and complexity of paperwork required to administer the Charity was also proving burdensome. And of course, in the meantime economic circumstances had improved dramatically, and the state was now here to help. The question was how to make things more manageable whilst following the purpose of the Charity.

Nine years later, the Charities Act 1985 came into law. It permitted small charities like this to be wound up. It took a while, but in early 1994 a letter notified the trustees that the Charity had at last been officially closed down, and a useful sum had accumulated that could, as its final act, be distributed in the spirit that its founder intended.

Simon Mainwaring

From early times the richness and fertility of the land have attracted people to the location we now know as Great Canfield. A great diversity of relics has been unearthed, with the earliest a Neolithic polished stone axehead, dating from 3,500 BC. Artefacts from Celtic times and the Roman occupation onwards have been found in quantity. Many of these are in private collections and some are held in Saffron Walden Museum.

There is also archaeological evidence of Roman settlement, unsurprising as Great Canfield lies between two Roman roads that converge not far away. Hundreds of years after their construction the Normans reused bricks from local Roman villas in the fabric of the church.

The name Canfelda probably derived from "field of canes or reeds", perhaps linked with the marshy ground of the Roding valley. George Eland in his book "At the Courts of Great Canfield" suggested that the name Thorpe (Hope) End, a name retained into the C19th, hints at Danish occupation of that hamlet in 878. The Domesday Book of 1085 makes it clear that at the time of the Norman invasion Canfield formed a small part of the vast estates owned by Ulwine, a great Saxon thane.

Shortly afterwards Alberic de Vere was awarded the manor, and it remained in his family (later the Earls of Oxford) for five hundred years. The Normans built the castle mound, its outer bailey dating back to the early C12th, and the adjacent church of St Mary. The castle buildings were of wood. They and the palisades that surrounded them disappeared long ago, probably reapplied to dwellings elsewhere in Great Canfield. The farms around the church were demesne lands (farmed by serfs on behalf of the Lord of the Manor and not tenanted). The Hall, Canfield Bury and Marsh Farm now occupy some of that area.

Inside the church, acknowledged as a perfect example of Norman architecture, is a C13th mural of the Virgin and Child. In the porch are carvings from Norse mythology, adopted for Christian use, including Odin with his ravens Hugin and Mugin and depictions of a form of swastika, an ancient symbol also known as a fylfot cross.

The Parish and Manor seem always to have coincided in extent and the surviving manorial rolls help to explain the growth of the village over time. As the settlement evolved it developed a pattern still recognisable today. The Hart and Frith (or Thrift) Woods, both classified as Ancient Woodland, are now much diminished. They, together with the enclosed deer park which extended around Canfield Park House offered important economic rights and resources. Other woodland was cleared and the field system grew. In mediaeval times, large open fields ran down the middle of the village to the north and east of Green Street, with Bexley (or Boxley) Common to the west of it. Some of the ancient field names are still used.

After the C12th there is no evidence of any nucleus or dominant area, with a handful of farms and agricultural workshops being scattered throughout the Parish. Over the centuries, the seven distinct hamlets or Ends evolved around the farms, crofts and woods. The sketch at the foot of the page (from 60 years ago) shows the principal historical locations in the village, which survive to today with open countryside between them.

The church was always an important focus for the community but even in the Victorian period while almshouses lay close by the church, the inn, school and rectory were all situated separately from it. Shops, forge, maltings and post-office have all changed their locations over time. The stocks and whipping-post were situated centrally at Hellman’s Cross and The Griffin Inn was part of what is now The Grange.

As now, houses generally sat within their own plots, the majority accessed directly from the main lanes though often set back from them. Most originated as farmhouses or farm cottages, although the former were often divided into tenements in Victorian times. Until the break-up of the Maryon-Wilson Estate in 1900, few were owner-occupied.

It appears that from very early times the village adopted the linear character it still possesses. Its lanes linked the common lands and discrete parts of the manor with the major highway at Stane Street (now the B 1256), to the thriving market town of Hatfield Broad Oak and its Benedictine Priory, and other neighbouring settlements. In later centuries those lanes also provided links to Maryon-Wilson properties in other parishes, for example Langthorns in Little Canfield. A drove road is said to have originally run past The Elms which at one time sold ale to those who passed. As late as 1908 a new road was cut linking Bacon End with the railway station at Little Easton Lodge.

Within living memory the village still had a pub, school, post office, forge and shop but all have now reverted to other uses. Many houses large and small have been renamed. Others have simply disappeared, even quite recently, for example Whitebridge in Oak Lane where George Eland lived and wrote in the 1940s. There remain many other signs of earlier settlement in the form of listed dairies, pumps, dove-houses, model farm buildings, barns, and even a brick icehouse. Satellite photographs also reveal the outline of a windmill which was destroyed around 1900.

The People

By the time of Domesday the manor supported about 100 people including serfs. Tenant farmers were obliged to cultivate de Vere’s land but were also able to rent land for themselves and use the common land for grazing animals.

The records of the manorial court start in 1346, the year of the Battle of Crécy. They end in 1668, giving perspective over more than three hundred years of Great Canfield history. Occasionally the village felt the impact of great events from outside: most notably the records give evidence of exceptional mortality around the time of the Black Death in 1349. Otherwise they dealt with preoccupations arising locally. Apart from the odd assault and theft, most had to do with the land.

In the late C16th, the Wisemans acquired the title of Lords of the Manor. In the early C18th the title passed to the Peers family and from there by marriage and descent to the Maryon-Wilsons, who had acquired many holdings in the Parish. A family member still holds the title of Lord of the Manor.

Two books add detail on Great Canfield’s history. George Eland’s outlines findings from the manorial court rolls and discusses particular houses built during that time. Raleigh Trevelyan’s "A Hermit Disclosed" examines the life of Jimmy Mason, a recluse in Great Canfield, through the diary he kept a century and a half ago.

Great Canfield developed as a flourishing agricultural community. The population peaked at 520 in the early C19th. The census of 1831 showed virtually all working within the Parish and 80% of its working population still on the land. White’s Directory of Essex from 1848 describes Great Canfield as "a pleasant village … has in its Parish 496 souls and 2,471 acres of land". The Directory provides a list of inhabitants. It includes in addition to those working on the land a carpenter, victualler, wheelwright, shopkeeper, blacksmith, bricklayer, corn miller, tailor, vicar, and the squire. To these the Post Office Directory of 1874 adds a schoolmistress, shoemaker and farm bailiff to manage the squire’s estates – virtually everybody at that time still finding employment within the village.

In 1825 there were 93 houses in Great Canfield and by 1875 this number had risen to 122. It declined to 75 in the 1920s, possibly as divided tenements were once more combined into single dwellings whilst others just collapsed. From then on the number rose steeply again to the current 144 with much of this growth taking place in Hope End.

Great Canfield Today

Great Canfield has five main points of entry and is separated from its neighbouring villages by open farmland. The majority of houses back onto or are surrounded by agricultural land. This rural setting is greatly valued by the community, who strongly oppose urbanisation in its various forms.

Great Canfield remains a rural village, albeit one under pressure from urban development. Particularly in the Hope End and Bacon End areas, actual and planned developments in Takeley and Little Canfield grow ever closer.

At the time of the last census in 2001, there were 139 homes, including 3 council-owned and 23 privately rented with the remainder owner-occupied. Since that time there have been a number of barn conversions. The total number of homes has now risen to 144.

In 2001 there were 110 detached houses or bungalows, and 29 terraced or semi-detached residences. Of the total population of 364, 196 were male and 168 female. The age profile of Great Canfield’s residents was very similar to other local towns and villages. The current electoral register shows 311 voters.

A great demographic change occurred as agriculture shed its large labour force, and many houses originally occupied by farming or ancillary workers were no longer required for that purpose. Today the great majority of residents in work find employment outside the village and in the absence of any regular public transport, 96% of households have a car and 76% have two or more.

Great Canfield, as we were; The Vane Charity

In June 1866 the executors of the Reverend Frederick Vane invested £50 in three per cent annuities. The income was to be applied for the poor of the Parish of Great Canfield: on St Thomas’ Day, 21st December, a traditional day of charity in England and the shortestday of the year.

The population of Great Canfield 150 years ago was just under 500, 35% more than today. Virtually everyone worked within the Parish and 80% laboured on the land. Few people were likely to have had much money and life would have been pretty uncomfortable for some.

The Vane Charity was now able to help. Records for the Charity, contained in a small ruled exercise book, shed more light. Help was given mainly in coal. The first entry, on St Thomas’s Day 1866, had a half-year’s dividend of 17s 5d to distribute. “Coals to widows” accounted for 16s 6d and “Balance to Holdgate” the remaining 11d (d = old pence).

There are still Holdgates in the area. There appear many other family names, longstanding in the village and surrounding areas: Barker, Easter, Hayden, Perry, Reeve, Staines, Stock, and Lodge (probably the family of Isaac, born in 1866, who went on to win the Victoria Cross in the Boer War). Entries for male recipients in the early days usually just give surnames. Sometimes there is more to distinguish from others of the same name: Old Staines, Old Cliff, Blind Stock, Spellar’s boy, L Hayden. Many entries are generic: on St Thomas’ Day in 1869 the Charity gave 1ó hundredweight (76 kg) of coals each to “10 widows, 3 widowers and 5 sick people”. Sadly, there is no reference to where

anyone lived.

The yearly income of £1 14s 10d went a long way. One hundredweight of coal cost 1s 3d, a factor of about two hundred times less than today. The price hadn’t changed in 1906, when records in the exercise book ceased. There are few surviving records for a long time after 1906, but thanks to 70 years’ inflation the yearly income by 1976 no longer went far at all. The general pattern was now to let funds accumulate for a while and then make a contribution towards meals or fuel. In correspondence with the Charity Commission the then Rector noted “the quarterly interest, at present 36p, has been held as so small as to be incapable of regular distribution”. The volume and complexity of paperwork required to administer the Charity was also proving burdensome. And of course, in the meantime economic circumstances had improved dramatically, and the state was now here to help. The question was how to make things more manageable whilst following the purpose of the Charity.

Nine years later, the Charities Act 1985 came into law. It permitted small charities like this to be wound up. It took a while, but in early 1994 a letter notified the trustees that the Charity had at last been officially closed down, and a useful sum had accumulated that could, as its final act, be distributed in the spirit that its founder intended.

Simon Mainwaring